Leading Transition; a new model for change

Background

Change is nothing new to leaders, or their constituents. We understand by now that organisations cannot be just endlessly “managed,” replicating yesterday’s practices to achieve success. Business conditions change and yesterday’s assumptions and practices no longer work. There must be innovation, and innovation means change.

Yet the thousands of books, seminars, and consulting engagements purporting to help “manage change” often fall short. These tools tend to neglect the dynamics of personal and organisational transition that can determine the outcome of any change effort. As a result, they fail to address the leader’s need to coach others through the transition process. And they fail to acknowledge the fact that leaders themselves usually need coaching before they can effectively coach others.

In years past, perhaps, leaders could simply order changes. Even today, many view it as a straightforward process: establish a task force to lay out what needs to be done, when, and by whom. Then all that seems left for the organisation is (what an innocent sounding euphemism!) to implement the plan. Many leaders imagine that to make a change work, people needed only to follow the plan’s implicit map, which shows how to get from here (where things stand now) to there (where they’ll stand after the plan is implemented). “There” is also where the organisation needs to be if it is to survive, so anyone who has looked at the situation with a reasonably open mind can see that the change isn’t optional. It is essential.

Fine. But then, why don’t people “Just Do It“? And what is the leader supposed to do when they Just Don’t Do It — when people do not make the changes that need to be made, when deadlines are missed, costs run over budget, and valuable workers get so frustrated that when a head-hunter calls, they jump ship. Leaders who try to analyse this question after the fact are likely to review the change effort and how it was implemented. But the details of the intended change are often not the issue. The planned outcome may have been the restructuring of a group around products instead of geography, or speeding up product time-to-market by 50 percent. Whatever it was, the change that seemed so obviously necessary has languished like last week’s flowers.

That happens because transition occurs in the course of every attempt at change.Transition is the state that change puts people into. The change is external (the different policy, practice, or structure that the leader is trying to bring about), while transition is internal (a psychological reorientation that people have to go through before the change can work).

The trouble is, most leaders imagine that transition is automatic — that it occurs simply because the change is happening. But it doesn’t. Just because the computers are on everyone’s desk doesn’t mean that the new individually accessed customer database is transforming operations the way the consultants promised it would. And just because two companies (or hospitals or law firms) are now fully “merged” doesn’t mean that they operate as one or that the envisioned cost savings will be realised. Even when a change is showing signs that it may work, there is the issue of timing, for transition happens much more slowly than change. That is why the ambitious timetable that the leader laid out to the board turns out to have been wildly optimistic: it was based on getting the change accomplished, not on getting the people through the transition. Transition takes longer because it requires that people undergo three separate processes, and all of them are upsetting.

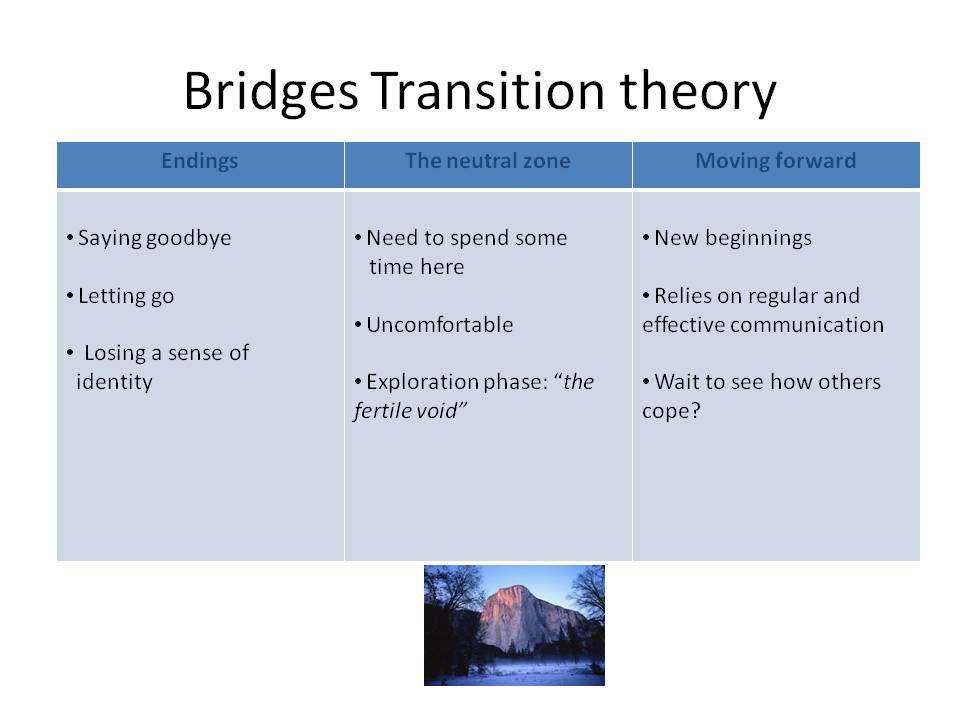

Saying Goodbye (endings)

The first requirement is that people have to let go of the way that things — and, worse, the way that they themselves — used to be. As the folk-wisdom puts it, “You can’t steal second base with your foot on first.” You have to leave where you are, and many people have spent their whole lives standing on first base. It isn’t just a personal preference you are asking them to give up. You are asking them to let go of the way of engaging or accomplishing tasks that made them successful in the past. You are asking them to let go of what feels to them like their whole world of experience, their sense of identity, even “reality” itself.

The first requirement is that people have to let go of the way that things — and, worse, the way that they themselves — used to be. As the folk-wisdom puts it, “You can’t steal second base with your foot on first.” You have to leave where you are, and many people have spent their whole lives standing on first base. It isn’t just a personal preference you are asking them to give up. You are asking them to let go of the way of engaging or accomplishing tasks that made them successful in the past. You are asking them to let go of what feels to them like their whole world of experience, their sense of identity, even “reality” itself.

On paper it may have been a logical shift to self-managed teams, but it turned out to require that people no longer rely on a supervisor to make all decisions (and to be blamed when things go wrong). Or it looked like a simple effort to merge two workgroups, but in practice it meant that people no longer worked with their friends or reported to people whose priorities they understood.

Shifting into Neutral

Even after people have let go of their old ways, they find themselves unable to start anew. They are entering the second difficult phase of transition. We call it the neutral zone, and that in-between state is so full of uncertainty and confusion that simply coping with it takes most of people’s energy. The neutral zone is particularly difficult during mergers or acquisitions, when careers and policy decisions and the very “rules of the game” are left in limbo while the two leadership groups work out questions of power and decision making.

Even after people have let go of their old ways, they find themselves unable to start anew. They are entering the second difficult phase of transition. We call it the neutral zone, and that in-between state is so full of uncertainty and confusion that simply coping with it takes most of people’s energy. The neutral zone is particularly difficult during mergers or acquisitions, when careers and policy decisions and the very “rules of the game” are left in limbo while the two leadership groups work out questions of power and decision making.

The neutral zone (“the fertile void”)

The neutral zone is uncomfortable, so people are driven to get out of it. Some people try to rush ahead into some (often any) new situation, while others try to back-pedal and retreat into the past. Successful transition, however, requires that an organisation and its people spend some time in the neutral zone. This time in the neutral zone is not wasted, for that is where the creativity and energy of transition are found and the real transformation takes place. It’s like Moses in the wilderness: it was there, not in the Promised Land, that Moses was given the Ten Commandments; and it was there, and not in The Promised Land, that his people were transformed from slaves to a strong and free people.

Today, it won’t take 40 years, but a shift to self-managed teams, for instance, is likely to leave people in the neutral zone for six months, and a major merger may take two years to emerge from the neutral zone. The change can continue forward on something close to its own schedule while the transition is being attended to, but if the transition is not dealt with, the change may collapse. People cannot do the new things that the new situation requires until they come to grips with what is being asked.

Moving Forward (new beginnings)

Some people fail to get through transition because they do not let go of the old ways and make an ending; others fail because they become frightened and confused by the neutral zone and don’t stay in it long enough for it to do its work on them. Some, however, do get through these first two phases of transition, but then freeze when they face the third phase, the new beginning. For that third phase requires people to begin behaving in a new way, and that can be disconcerting — it puts one’s sense of competence and value at risk. Especially in organisations that have a history of punishing mistakes, people hang back during the final phase of transition, waiting to see how others are going to handle the new beginning.

Some people fail to get through transition because they do not let go of the old ways and make an ending; others fail because they become frightened and confused by the neutral zone and don’t stay in it long enough for it to do its work on them. Some, however, do get through these first two phases of transition, but then freeze when they face the third phase, the new beginning. For that third phase requires people to begin behaving in a new way, and that can be disconcerting — it puts one’s sense of competence and value at risk. Especially in organisations that have a history of punishing mistakes, people hang back during the final phase of transition, waiting to see how others are going to handle the new beginning.

Extract from Berlin, Eaton & Associates Ltd. article; for the full article click here: WilliamBridgesTransitionandChangeModel