The “big 5” Personality traits

The Big The big five personality traits are the best accepted and most commonly used model of personality in academic psychology. The big five come from the statistical study of responses to personality items. Using a technique called factor analysis researchers can look at the responses of people to hundreds of personality items and ask the question “what is the best way to summarise an individual?”. This has been done with many samples from all over the world and the general result is that, while there seem to be unlimited personality variables, five stand out from the pack in terms of explaining a lot of a person’s answers to questions about their personality: extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience. The Big Five factors and their constituent traits can be summarized as an acronym of “OCEAN”:

- Openness to experience – (inventive/curious vs. consistent/cautious). Appreciation for art, emotion, adventure, unusual ideas, curiosity, and variety of experience.

- Conscientiousness – (efficient/organized vs. easy-going/careless). A tendency to show self-discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement; planned rather than spontaneous behaviour.

- Extraversion – (outgoing/energetic vs. solitary/reserved). Energy, positive emotions, urgency, and the tendency to seek stimulation in the company of others.

- Agreeableness – (friendly/compassionate vs. cold/unkind). A tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic towards others.

- Neuroticism – (sensitive/nervous vs. secure/confident). A tendency to experience unpleasant emotions easily, such as anger, anxiety, depression, or vulnerability.

The five broad factors were discovered and defined by several independent sets of researchers. These researchers began by studying known personality traits and then factor-analysing hundreds of measures of these traits (in self-report and questionnaire data, peer ratings, and objective measures from experimental settings) in order to find the underlying factors of personality.

The initial model was advanced by Ernest Tupes and Raymond Christal in 1961, but failed to reach an academic audience until the 1980s. In 1990, J.M. Digman advanced his five factor model of personality. These five over-arching domains have been found to contain and subsume most known personality traits and are assumed to represent the basic structure behind all personality traits.

Because the Big Five traits are broad and comprehensive though, they are not nearly as powerful in predicting and explaining actual behaviour as are the more numerous lower-level traits. Many studies have confirmed that in predicting actual behaviour the more numerous facet or primary level traits are more effective

When scored for individual feedback, these traits are frequently presented as percentile scores. For example, a Conscientiousness rating in the 80th percentile indicates a relatively strong sense of responsibility and orderliness, whereas an extraversion rating in the 5th percentile indicates an exceptional need for solitude and quiet. Although these trait clusters are statistical aggregates, exceptions may exist on individual personality profiles.

-

Openness to experience

Openness to experience is one of the domains which are used to describe human personality in the Five Factor Model. Openness involves active imagination, aesthetic sensitivity, attentiveness to inner feelings, preference for variety, and intellectual curiosity. A great deal of psychometric research has demonstrated that these qualities are statistically correlated. Thus, openness can be viewed as a global personality trait consisting of a set of specific traits, habits, and tendencies that cluster together.

Openness is a general appreciation for art, emotion, adventure, unusual ideas, imagination, curiosity, and variety of experience. People who are open to experience are intellectually curious, appreciative of art, and sensitive to beauty. They tend to be, compared to closed people, more creative and more aware of their feelings. They are more likely to hold unconventional beliefs. People with low scores on openness tend to have more conventional, traditional interests. They prefer the plain, straightforward, and obvious over the complex, ambiguous, and subtle. They may regard the arts and sciences with suspicion or even view these endeavours as uninteresting

Openness is a general appreciation for art, emotion, adventure, unusual ideas, imagination, curiosity, and variety of experience. People who are open to experience are intellectually curious, appreciative of art, and sensitive to beauty. They tend to be, compared to closed people, more creative and more aware of their feelings. They are more likely to hold unconventional beliefs. People with low scores on openness tend to have more conventional, traditional interests. They prefer the plain, straightforward, and obvious over the complex, ambiguous, and subtle. They may regard the arts and sciences with suspicion or even view these endeavours as uninteresting

Openness tends to be normally distributed with a small number of individuals scoring extremely high or low on the trait, and most people scoring near the average. People who score low on openness are considered to be closed to experience. They tend to be conventional and traditional in their outlook and behaviour. They prefer familiar routines to new experiences, and generally have a narrower range of interests.

People who are open to experience are no different in mental health from people who are closed to experience. There is no relationship between openness and neuroticism, or any other measure of psychological wellbeing. Being open and closed to experience are simply two different ways of relating to the world.

According to research by Sam Gosling, it is possible to assess openness by examining people’s homes and work spaces. Individuals who are highly open to experience tend to have distinctive and unconventional decorations. They are also likely to have books on a wide variety of topics, a diverse music collection, and works of art on display.

There are social and political implications to this personality trait. People who are highly open to experience tend to be politically liberal and tolerant of diversity. As a consequence, they are generally more open to different cultures and lifestyles

Sample openness items

- I have a rich vocabulary.

- I have a vivid imagination.

- I have excellent ideas.

- I am quick to understand things.

- I use difficult words.

- I spend time reflecting on things.

- I am full of ideas.

- I am not interested in abstractions. (reversed)

- I do not have a good imagination. (reversed)

- I have difficulty understanding abstract ideas.

-

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness is a tendency to show self-discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement against measures or outside expectations. The trait shows a preference for planned rather than spontaneous behaviour. It influences the way in which we control, regulate, and direct our impulses

Conscientiousness is the trait of being painstaking and careful, or the quality of acting according to the dictates of one’s conscience. It includes such elements as self-discipline, carefulness, thoroughness, organisation, deliberation (the tendency to think carefully before acting), and need for achievement. It is an aspect of what has traditionally been called character. Conscientious individuals are generally hard working and reliable. When taken to an extreme, they may also be workaholics, perfectionists, and compulsive in their behaviour. People who are low on conscientiousness are not necessarily lazy or immoral, but they tend to be more laid back, less goal oriented, and less driven by success.

Conscientiousness is the trait of being painstaking and careful, or the quality of acting according to the dictates of one’s conscience. It includes such elements as self-discipline, carefulness, thoroughness, organisation, deliberation (the tendency to think carefully before acting), and need for achievement. It is an aspect of what has traditionally been called character. Conscientious individuals are generally hard working and reliable. When taken to an extreme, they may also be workaholics, perfectionists, and compulsive in their behaviour. People who are low on conscientiousness are not necessarily lazy or immoral, but they tend to be more laid back, less goal oriented, and less driven by success.

People who score high on the trait of conscientiousness tend to be more organised and less cluttered in their homes and offices. For example, their books tend to be neatly shelved in alphabetical order, or categorized by topic, rather than scattered around the room. Their clothes tend to be folded and arranged in drawers or closets instead of lying on the floor. The presence of planners and to-do lists are also signs of conscientiousness. Their homes tend to have better lighting than the homes of people who are low on this trait.

Conscientiousness is importantly related to successful academic performance in students and workplace performance among managers and workers. Low levels of conscientiousness are strongly associated with procrastination. A considerable amount of research indicates that conscientiousness is one of the best predictors of performance in the workplace, and indeed that after general mental ability is taken into account, the other four of the Big Five personality traits do not aid in predicting career success. Conscientious employees are generally more reliable, more motivated, and harder working. Furthermore, conscientiousness is the only personality trait that correlates with performance across all categories of jobs. However, agreeableness and emotional stability may also be important, particularly in jobs that involve a significant amount of social interaction.

Although conscientiousness is generally seen as a positive trait to possess, recent research has suggested that in some situations it may be harmful for well-being. In a prospective study of 9570 individuals over four years, highly conscientiousness people suffered more than twice as much if they became unemployed. The authors suggested this may be due to conscientious people making different attributions about why they became unemployed, or through experiencing stronger reactions following failure.

Sample conscientiousness items

- I am always prepared.

- I pay attention to details.

- I get chores done right away.

- I like order.

- I follow a schedule.

- I am exacting in my work.

- I leave my belongings around. (reversed)

- I make a mess of things. (reversed)

- I often forget to put things back in their proper place. (reversed)

- I shirk my duties. (reversed)

-

Extroversion

Extroversion is characterized by positive emotions, urgency, and the tendency to seek out stimulation and the company of others. The trait is marked by pronounced engagement with the external world. Extroverts enjoy being with people, and are often perceived as full of energy. They tend to be enthusiastic, action-oriented individuals who are likely to say “yes!” or “let’s go!” to opportunities for excitement. In groups they like to talk, assert themselves, and draw attention to themselves.

Introverts lack the social exuberance and activity levels of extroverts. They tend to seem quiet, low-key, deliberate, and less involved in the social world. Their lack of social involvement should not be interpreted as shyness or depression. Introverts simply need less stimulation than extroverts and more time alone. They may be very active and energetic, simply not socially.The trait of extroversion-introversion is a central dimension of human personality theories.

Introverts lack the social exuberance and activity levels of extroverts. They tend to seem quiet, low-key, deliberate, and less involved in the social world. Their lack of social involvement should not be interpreted as shyness or depression. Introverts simply need less stimulation than extroverts and more time alone. They may be very active and energetic, simply not socially.The trait of extroversion-introversion is a central dimension of human personality theories.

Extroverts tend to be gregarious, assertive, and interested in seeking out external stimulus. Introverts, in contrast, tend to be introspective, quiet and less sociable. They are not necessarily loners but they tend to have fewer numbers of friends. Introversion does not describe social discomfort but rather social preference: an introvert may not be shy but may merely prefer fewer social activities. Ambiversion is a balance of extrovert and introvert characteristics. Most people (about 68% of the population) are considered to be ambiverts, while extroverts and introverts represent the extremes on the scale, with about 16% representation for each.

The terms introversion and extroversion were first popularized by Carl Jung. Virtually all comprehensive models of personality include these concepts. Examples include Jung’s analytical psychology, Eysenck’s three-factor model, Cattell’s 16 personality factors, the Big Five personality traits, the four temperaments and the Myers Briggs Type Indicator.

Sample extroversion items

- I am the life of the party.

- I don’t mind being the centre of attention.

- I feel comfortable around people.

- I start conversations.

- I talk to a lot of different people at parties.

- I don’t talk a lot. (reversed)

- I keep in the background. (reversed)

- I have little to say. (reversed)

- I don’t like to draw attention to myself. (reversed)

- I am quiet around strangers. (reversed)[33]

-

Agreeableness

Agreeableness is a tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic towards others. The trait reflects individual differences in general concern for social harmony. Agreeable individual’s value getting along with others. They are generally considerate, friendly, generous, helpful, and willing to compromise their interests with others. Agreeable people also have an optimistic view of human nature. They believe people are basically honest, decent, and trustworthy.

Disagreeable individuals place self-interest above getting along with others. They are generally unconcerned with others’ well-being, and are less likely to extend themselves for other people. Sometimes their scepticism about others’ motives causes them to be suspicious, unfriendly, and uncooperative.

Disagreeable individuals place self-interest above getting along with others. They are generally unconcerned with others’ well-being, and are less likely to extend themselves for other people. Sometimes their scepticism about others’ motives causes them to be suspicious, unfriendly, and uncooperative.

Agreeableness is a tendency to be pleasant and accommodating in social situations. In contemporary personality psychology, agreeableness is one of the five major dimensions of personality structure, reflecting individual differences in concern for cooperation and social harmony.People who score high on this dimension are empathetic, considerate, friendly, generous, and helpful. They also have an optimistic view of human nature. They tend to believe that most people are honest, decent, and trustworthy.

People scoring low on agreeableness are generally less concerned with others’ well-being, report less empathy, and are therefore less likely to go out of their way to help others. Their scepticism about other people’s motives may cause them to be suspicious and unfriendly. People very low on agreeableness have a tendency to be manipulative in their social relationships. They are more likely to compete than to cooperate.

The research also shows that people high in agreeableness are more likely to control negative emotions like anger in conflict situations. Those who are high in agreeableness are more likely to use constructive tactics when in conflict with others, whereas people low in agreeableness are more likely to use coercive tactics. They are also more willing to give ground to their adversary and may “lose” arguments with people who are less agreeable. From their perspective, they have not really lost an argument as much as maintained a congenial relationship with another person.

A central feature of agreeableness is its positive association with altruism and helping behaviour. Across situations, people who are high in agreeableness are more likely to report an interest and involvement with helping others. Experiments have shown that whereas most people are likely to help their own kin, or when empathy has been aroused, agreeable people are likely to help even when these conditions are not present. In other words, agreeable people appear to be “traited for helping” and do not need any other motivations.

While agreeable individuals are habitually likely to help others, disagreeable people may be more likely to harm them. Researchers have found that low levels of agreeableness are associated with hostile thoughts and aggression in adolescents, as well as poor social adjustment.

Sample agreeableness items

- I am interested in people.

- I sympathize with others’ feelings.

- I have a soft heart.

- I take time out for others.

- I feel others’ emotions.

- I make people feel at ease.

- I am not really interested in others. (reversed)

- I insult people. (reversed)

- I am not interested in other people’s problems. (reversed)

- I feel little concern for others. (reversed)

-

Neuroticism

Neuroticism is the tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anger, anxiety, or depression. It is sometimes called emotional instability. Those who score high in neuroticism are emotionally reactive and vulnerable to stress. They are more likely to interpret ordinary situations as threatening, and minor frustrations as hopelessly difficult. Their negative emotional reactions tend to persist for unusually long periods of time, which means they are often in a bad mood. These problems in emotional regulation can diminish the ability of a person scoring high on neuroticism to think clearly, make decisions, and cope effectively with stress.

At the other end of the scale, individuals who score low in neuroticism are less easily upset and are less emotionally reactive. They tend to be calm, emotionally stable, and free from persistent negative feelings. Freedom from negative feelings does not mean that low scorers experience a lot of positive feelings.

Neuroticism is a fundamental personality trait in the study of psychology. It is an enduring tendency to experience negative emotional states. Individuals who score high on neuroticism are more likely than the average to experience such feelings as anxiety, anger, guilt, and depressed mood.They respond more poorly to environmental stress, and are more likely to interpret ordinary situations as threatening, and minor frustrations as hopelessly difficult. They are often self-conscious and shy, and they may have trouble controlling urges and delaying gratification. Neuroticism is a risk factor for “internalizing” mental disorders such as phobia, depression, panic disorder, and other anxiety disorders (traditionally called neuroses).

On the opposite end of the spectrum, individuals who score low in neuroticism are more emotionally stable and less reactive to stress. They tend to be calm, even-tempered, and less likely to feel tense or rattled. Although they are low in negative emotion, they are not necessarily high on positive emotion. Being high on positive emotion is an element of the independent trait of extraversion. Neurotic extraverts, for example, would experience high levels of both positive and negative emotional states, a kind of “emotional roller coaster”. Individuals who score low on neuroticism (particularly those who are also high on extraversion) generally report more happiness and satisfaction with their lives.

Sample neuroticism items

- I am easily disturbed.

- I change my mood a lot.

- I get irritated easily.

- I get stressed out easily.

- I get upset easily.

- I have frequent mood swings.

- I often feel blue.

- I worry about things.

- I am relaxed most of the time. (reversed)

- I seldom feel blue.

Taking the assessment

There are several sites where as part of ongoing research, you can take the assessment, and receive back an overview of your percentile scores in each of the 5 areas.

One link is here; another one that uses a slightly different interpretation in the answers with a graph is here

Extracts taken from from Psychometrictests.com

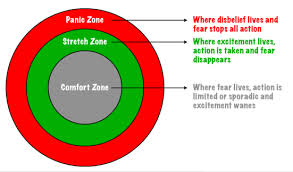

A worldwide pandemic, and coaching work with several people directly dealing with Covid 19, has got me thinking a lot about self-care. Self-care is an all-encompassing umbrella term for any activity we undertake that proactively looks after our mental, emotional and physical health. One definition says appropriately given current circumstances: “the practice of taking an active role in protecting one’s own well-being and happiness, in particular during periods of stress”.

A worldwide pandemic, and coaching work with several people directly dealing with Covid 19, has got me thinking a lot about self-care. Self-care is an all-encompassing umbrella term for any activity we undertake that proactively looks after our mental, emotional and physical health. One definition says appropriately given current circumstances: “the practice of taking an active role in protecting one’s own well-being and happiness, in particular during periods of stress”. Practicing self-care isn’t always easy. The speed of the modern world, the stress we have in busy lives at work and at home can all mitigate against the need to take time to ourselves. We talk about the idea of “work life balance” but in practice overwork or lack of work-life balance can make people less productive, disorganised and emotionally depleted. In coaching practice self-care comes up time and time again with clients; clients who run businesses and struggle with work-life balance, clients who are senior Managers in organisations dealing with huge pressure due to Covid, clients stuck doing jobs they don’t enjoy but have got boxed in by the salary expectations, or people operating at a senior level in organisations, where they have little “hinterland” of other interests outside of work.

Practicing self-care isn’t always easy. The speed of the modern world, the stress we have in busy lives at work and at home can all mitigate against the need to take time to ourselves. We talk about the idea of “work life balance” but in practice overwork or lack of work-life balance can make people less productive, disorganised and emotionally depleted. In coaching practice self-care comes up time and time again with clients; clients who run businesses and struggle with work-life balance, clients who are senior Managers in organisations dealing with huge pressure due to Covid, clients stuck doing jobs they don’t enjoy but have got boxed in by the salary expectations, or people operating at a senior level in organisations, where they have little “hinterland” of other interests outside of work. Universal wisdom seems to indicate that self-care needs to be something you actively plan, rather than something that just happens. It is an active choice and you should treat it as such.

Universal wisdom seems to indicate that self-care needs to be something you actively plan, rather than something that just happens. It is an active choice and you should treat it as such.